Davy’s First Shift Story Text

Download the Word Document: Davy’s First Shift Story Text (32 KB)

Hello! My name is Leslie, and I'm going to take you on a journey back in time, to the Victorian times, a time when some people worked and lived in mining villages here in Westoe, South Shields. To make your journey more fun, I would like you to help me tell this story by joining in, by creating sounds, noises, actions, and even tasting and smelling things. Don't worry: you can do as little or as much as you like; and if you prefer, you can just sit comfortably and listen.

You will need to gather the following items to take with you on your journey. Don't worry if you don't have everything; you can still use your hands, voices, and feet to make lots of noise, and there is plenty for you to join in with.

Right. Are you ready for your list?

You can write them down, and then stop this recording while you and your grown-ups go and find them.

It is a good idea to keep all your props close by.

OK. Are you ready for the list?

Number 1: A teaspoon, a saucepan, or a metal dish.

Number 2: A table, a window, or a book, to tap on.

Number 3: A sweet wrapper.

Number 4: A shirt or a pair of jeans.

Number 5: A straw and a cup of water.

Number 6: A cup or a mug.

Number 7: A clean pair of shoes.

Number 8: A saucepan lid or a metal oven tray.

Number 9: A plastic box.

Number 10: A snack, some toast, or biscuits would be fine.

[Pause here while you collect your props.]

Hello again. Are your props in front of you?

Your grown-up can help with handing you things and joining in.

I love to tell stories that are packed with sensory activities to help you bring it to life.

So let's get started.

[Story begins.]

Our story is set in the 1900’s, in the cold of winter, and begins in the early hours of the morning and continues through until teatime.

It is based in Davy’s pit cottage, and in and around the pit village of Westoe, South Shields.

It's 3:00 AM. Davy is startled by the ringing of the alarm clock from the room of his parents.

Grab your teaspoon and tap it on a saucepan or metal dish to make the sound of the alarm clock.

[Alarm clock sound.]

He shares his bed with his two younger brothers.

He has lain awake for some time, thinking of what the next hours will bring.

Although he belongs to a coal mining family, and is familiar with pit talk, with its unique terminology, he still has a feeling of dread of what will be his first day down a coal mine.

Davy is 12 years old, and he will be underground for 12 hours.

His thoughts are interrupted by the gentle but firm hand of his father.

“Time to get up, son”, his father whispers, so as not to wake his three older brothers, who also share the room.

They also work at the pit.

There is a tapping on the steamed-up window from the pole of the knocker-up, a person who was paid a small amount from the miners who are on the early shift that live in the streets of the terraced houses that surround the pit, to make sure they do not oversleep.

Why don't you try and be a knocker-up, by tapping on a window, table, or book now?

[Knocking sound.]

Davy rubs his sleep from his eyes, puts on the clothes that will soon become his work-wear, most of which are hand me downs from his older brothers.

Here you can have a go at one of these sounds. You can either:

- crackle a sweet wrapper for the fire; [Crackling sound.]

- flap a bit of material for the flame, by using a shirt sleeve or a pair of jeans; [Flapping sound.]

- blow bubbles with a straw in a cup of water, or use a teaspoon in a cup or mug to stir the tea. [Stirring sound.]

Downstairs Davy joins his father at the table in front of the roaring coal fire.

His mother pours the bubbling, boiling water from the large, blackened kettle into a brown China teapot, and gives it a brisk stir.

The kettle is returned to the hob of the cast-iron fireplace with a loud metallic clank. Then, with the iron poker, she stokes up the red-hot coals, sending sparks flying up the chimney.

Did you make the noise for the flame? Did you stir the tea in the mug?

Between slurps of tea filtering through his moustache, munching on a slice of dripping bread, his father tells him what to expect in his new job.

Although he is familiar with pitmatic speak, Davy listens intently.

At one end of the table, three bait tins have already been filled with thick stottie cake and jam sandwiches, alongside three tin bottles filled with cold tea.

One set is for an older brother on a later shift.

As father and son leave for the mine, Mother looks at her son, who must soon become a man in the dangerous environment of the coal mine.

Here you can have a go at making the sound of the clogs, by knocking your knuckles on the table, or use your feet where you are sitting or standing, or even put a clean pair of shoes on your hands and pretend to walk them on the table.

[Clog sound.]

Father and son join the crowd of fellow pitmen hunched over with heads bowed against the biting winter morning wind. Their metal-studded clogs resounding on the frost-covered cobbled road as they marched silently to the mine.

He has seen the headgear of the colliery almost every day of his young life, night and day, summer and winter, but it never looked so daunting as now, with the headgear and winding-engine house silhouetted against the cold, moonlit sky, and its thick steel ropes drawing coal up from the mine.

Steam and smoke belch from the tall boiler house chimneys, where the coal-fired furnaces provide the energy to drive the huge steam-driven winding-engine, adding to the noise of metal on metal as coal trucks are moved around the pit yard.

Let's try to make the rattling sounds of the coal truck with a saucepan and lid, or a metal oven tray and a spoon. You could even put a few spoons inside the oven tray and swish them about.

[Rattling sound.]

Despite his tender years, young Davy is well known by many of the miners, and receives many words of encouragement, making him feel part of a great family bonded together by danger.

Davy and his father arrive at the office and clock in. Next they go to the lamp cabin, where his father collects his lamp, and Davy is given a candle.

At the pithead, the miners await the arrival of the cage, that can be heard rattling up the shaft. It slows, then bounces to a halt, suspended on the four heavy chains attached to the steel rope.

The banksman removes the metal gate from the first deck, each one the height of a coal tub, with just enough room for eight crouching men.

They enter, squat down, facing each other.

The metal gate is replaced and the cage is lowered, stopping to collect more men.

The cage loaded, the banksman signals the winding house by the bell system, and it descends slowly, gathering speed, rattling and bumping against the greased wooden guides that line the walls of the cage shaft.

Try that rattling sound again, with a saucepan and lid, or a metal oven tray and a spoon.

[Rattling sound.]

Davy finds his father’s hand, and receives a reassuring squeeze. He feels much better.

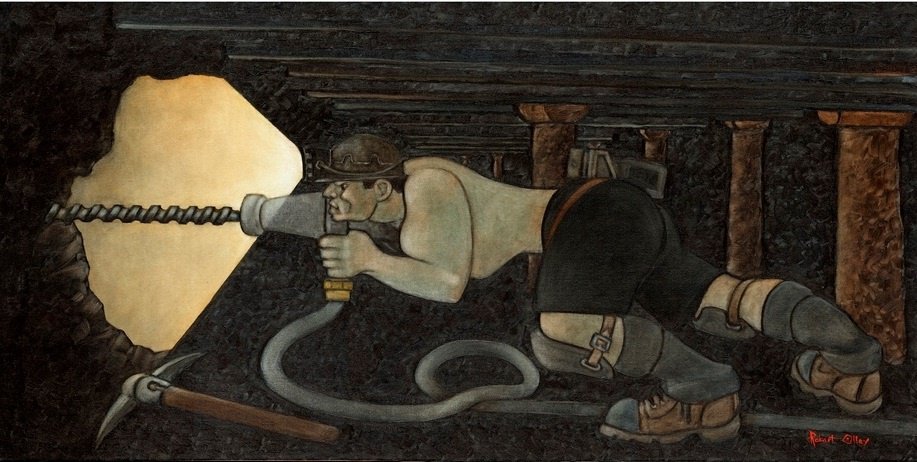

At the shaft bottom, Davy is introduced to his overseer, and is told that his job will be that of a trapper boy, the person who opens and closes the wooden doors that control the airflow in the mine.

Davy, his father, and a dozen or so miners leave the shaft bottom and travel a mile into the coalface.

Davy’s place of work is a tunnel two metres high by two metres wide. The roof is supported by thick wooden pit props, and there is a single narrow rail-track that leads beyond the wooden air door.

He will sit in the dark.

His only light is from the candle he was given.

During his 12-hour shift, he must listen for the putter and his pony pulling two or three full tubs of coal, opening and closing the air doors to let them out, and doing the same when the putter returns with empty tubs.

If his candle goes out, he will spend the rest of his shift in total darkness.

Young Davy took up his post and tried to make himself comfortable in the eerie light, listening for any approaching ponies. In the total silence, he could hear the occasional creaking of the timber roof supports, reminding him where he was and what was above him.

Mice scurried and squeaked around him, their orange eyes reflecting the light from his candle.

Can you make the sound of a squeaking mouse?

[Squeaking sound.]

The sound of tubs rattling along the rail-track signalled the arrival of his first customer, bringing empty tubs to the coalface where the hewers were working.

Hewers were the Royals of the mine, lean fit men, usually aged between 20 and 30, and paid on the amount of coal they collected.

There's that rattle again. Can you get your saucepan and lid or metal oven tray again to make that sound?

[Rattling sound.]

Or, find a plastic box and drum on it with your hands.

Davy was about to learn his first lesson.

Although the putter was a family friend, he yelled at Davy not to wait until the pony stopped before opening the air door. The putter hurriedly explained that his and the wages of the hewers at the coalface depended on the amount of coal they collected on each shift: waiting for the pony to stop slowed the men down.

Halfway through the shift, after finishing his bait, he felt himself nodding off to sleep, a cardinal sin down a coal mine.

He decided to get up and explore his surroundings, only to be confronted by a deputy, who scolded him strongly about the consequences of leaving his post.

Another lesson learned.

At the end of the shift, the air doors opened, and the teams of hewers appeared, a mixture of coal dust and sweat covering their lean, muscular bodies.

Davy looked in awe, and instantly decided what he wanted to be: a real pitman, a hewer, a Royal.

He tagged along behind the group, listening to their pitmatic chat, happy that he had completed his first shift.

At the shaft bottom, he was reunited with his father. It was dusk when they left the pit yard, passing the men of the next shift talking and joking. His chest swelled when one or two recognized him, even with coal dust on his face, and shouted,

“You're a real pitman now, Davy.”

Here you might like to get your snack of toast or biscuits to enjoy while you're listening to the end of the story. Also, get your sweet wrapper again to make the sound of the fire coming up.

They arrived home to the warmth of a roaring coal fire.

His mother had two places set on the wooden table. In the middle was a large pot of steaming broth and a plate of freshly baked stottie cake.

As his mother ladled out the helpings of broth, Davy spoke in great detail about his experiences as a coal miner to his wide-eyed younger brothers.

“Get some more down you, son. That'll stick your belly to your back”, his father said jokingly, as he watched his son enjoy his first meal as a worker.

The tin bath was placed in front of the roaring fire, on which a large pan of water heated. Normally, his father would wash first, but the honour was given to the new worker as it was his first shift.

Washed and dried and with drooping eyelids, Davy retired to bed and fell into a deep sleep.

At 3:00 AM, the alarm clock sounded once again.

It's back to the beginning with your teaspoon and saucepan to make the sound of the alarm clock.

[Alarm clock sound.]